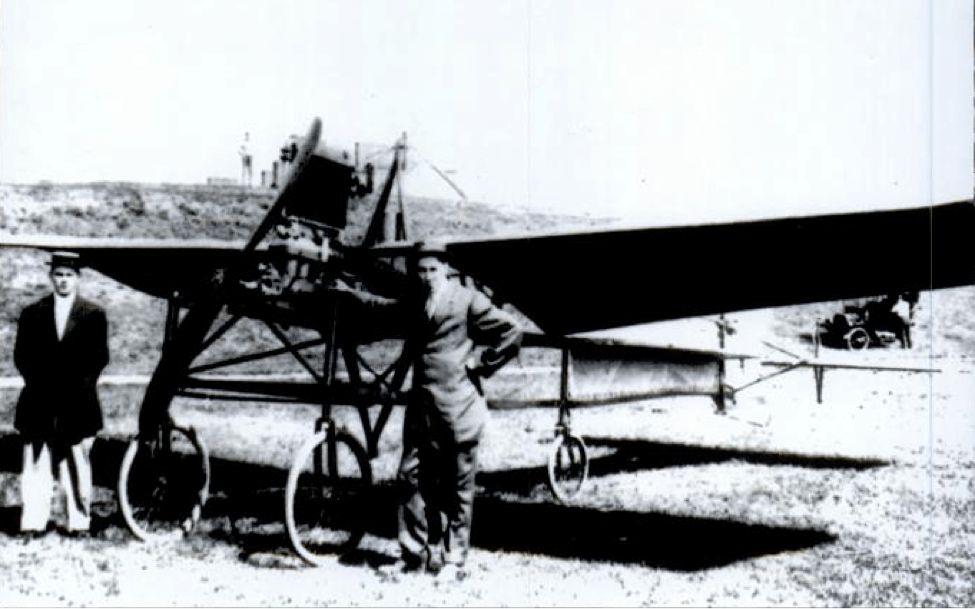

Henry Ford’s interest in aviation predates the 1926 launch of the famous Tri-Motor by nearly two decades. In 1908, the then 42-year-old Ford made history with the launch of the Model T. Ford achieved his goal of a car for the masses and a few years later, those cars would be built using a then novel moving assembly line. Ford wasn’t first to make an automobile assembly line–Ransom Olds beat him by over a decade–but it allowed the Ford Motor Company to crank out cars at an incredible rate. But while Ford was working on his cars, he was also getting interested in aviation. An early example of Ford’s interest in aviation was in helping his son, Edsel, build a plane. As the book Beyond the Model T : the other ventures of Henry Ford, writes, Ford rented a small barn on Woodward Avenue in Detroit. In the barn, he built tractors using Model T parts. Edsel and friend Charles Van Auken wanted to build a plane, and Ford gave the pair a trio of shop employees to build it. Van Auken designed the aircraft, with Edsel assisting in research and helping to build it. The resulting plane was powered by a Model T’s engine making 28 HP and roll control was achieved by bending the wings. It never flew any higher than ground effect and crashed both times that Van Auken tried to fly it. In 1917, the book describes, Ford got involved with another aircraft. This one was incredible in scope for its day. Charles F. Kettering, Orville Wright, Elmer Sperry, Ford, and others embarked on a secret project to create what was more or less a flying torpedo. The Kettering Bug was an unmanned aircraft capable of delivering a bomb 75 miles away. Navigation was handled with a pneumatic and electrical system. The National Museum of the United States Air Force describes how it worked: According to a study on cruise missiles, The Evolution of the Cruise Missile, when the military tested the Kettering Bug few tests were successful and it never saw combat. That wasn’t Ford’s only venture during World War I. His company also built Liberty aircraft engines. Ford was even interested in airships. In 1920, he offered to build airships for the U.S. government, but the deal didn’t go through. Later, Ford and his son invested in airship projects and even built a private airship mooring. Around this time, Ford also invested in the Stout Metal Airplane Company before buying it out in 1925. As we know, this would result in the famous Ford Tri-Motor that I got to take a ride in. Ford also planned on taking the success of the Model T and replicating it in the sky. The Flivver, which made its first appearance in 1926, was supposed to be a plane that everyone can afford and everyone can fly. Amazingly, throughout all of this time, Henry Ford had never flown in an aircraft. As the Experimental Aircraft Association notes, when Ford purchased Stout, he said: While the Tri-Motor was an important first step towards safer flying, it would take several decades for commercial aviation to reach the levels of safety that travelers enjoy today. Perhaps the more incredible thing about it was that not only did Ford not fly in a plane, but he actively refused to. That changed when Charles A. Lindbergh visited Ford Airport. Just a few months earlier, Lindbergh wrote history by completing the first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight.. On May 20, 1927 his aircraft, the Spirit of St. Louis, lifted from the ground of Roosevelt Field in New York. It touched down 33 and a half hours later at Le Bourget Field in Paris. In August 1927, Lindbergh was on a promotional tour for his historic flight and made a stop to Ford Airport. While there, history site HistoryNet notes, Lindbergh offered to take Ford up in the Spirit of St. Louis. Lindbergh expected Ford to decline, but to everyone’s surprise, he said yes. Here was the flight from Lindbergh’s perspective, from HistoryNet: Lindbergh’s plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, was built specifically for the task of being flown as far as possible. It had just a single seat inside for Lindbergh. So for the flight, a seat was crammed inside and Ford somehow folded himself into the thing. And for Ford’s perspective, here’s what he said in an interview with the New York Times: After taking Ford for his first flight, Lindbergh later took the rest of the family into the sky in the Spirit of St. Louis. It’s not reported why Ford didn’t want to fly before this, but apparently he had so much fun that he let Lindbergh take him for a spin in a new Ford Tri-Motor. I absolutely felt no sensation of uneasiness, with the exception of a few little air bumps which we encountered not and then, principally because we were flying over the city, the heat of which causes the air disturbances. This was the finest ride I ever had. Why, it is just like going on a picnic.” It isn’t said what Ford’s flying life looked like after this, but it sounds like he was impressed. Unfortunately, Ford’s vision of young people flying around in the Model T of planes never really materialized. Remember the Flivver from earlier? Its chief test pilot, Harry J. Brooks, died crashing a prototype Flivver in 1928. Just two were ever built, and Ford was apparently devastated enough by Brooks’ death that development was halted. As I noted in my article about the Tri-Motor, in the 1930s Ford faced headwinds from other competent airliner designs. Sales fell during the Great Depression and eventually, production stopped after 199 were built. The Stout Metal Airplane Division of the Ford Motor Company tried its hand at a couple of more aircraft designs that never reached production. Then in 1936, Ford closed Stout and stopped designing aircraft. The Ford name would be seen again in aviation fewer than ten years later. As part of its WWII effort, Ford produced 8,685 Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers and 4,190 Waco CG-4 gliders. Ford doesn’t design or produce planes today, but the company is a sponsor of the EAA AirVenture Oshkosh fly-in. Of course, he was also cantankerous, and he might have done it just to keep those lackeys around him on their toes and prove that he wasn’t timid/predictable/laughing stock/whatever boogieman feeling. If Lindbergh asked you to go for a flight with him in the Spirit of St Louis, what would you say? What if Jordan asked if you wanted to join a pickup game? Or Tiger asked if you wanted to hit the driving range? No brainer. The History Guy has a short yt video about him. Way worth ~10 min of your life The result was Whitman getting added to Ford’s summertime van-life thing (as it was back then, complete with servants) where he, Thomas Edison, and Harvey Firestone would drive around the country together, chatting up the locals and raising hell. Riffing on what others have already noted, Ford was a complex man for sure. Color me appropriately schooled for today – thanks for setting me straight! I’m hoping I get moved back there in a year or two and I’ll be more than happy to show you and the wife around, introduce you to some aviation geek friends we have there. One does historical aviation restoration which I think would be your speed for sure! Also, welcome COMTNDRVR! I love seeing some familiar names around here. 🙂