[Editor’s Note: I’m so excited to have the legendary Jonee Eisen writing some in-depth things for us! Jonee is an Associate Curator at the Petersen Automotive Museum and has owned over 60 cars over the years, all sorts of rare and strange and wonderful things. Seeking out Jonee to trade drives in his microcars for a drive in my Scimitar back in 2007 partially started me down the auto-writing path, even. Many of you will know his in-depth research works from the old Oppositelock, and I’m hoping we’ll continue to have more here. Oh, and he also once wrote an alien sex movie that had Moby in it. Enjoy. – JT] Renzo Rivolta was the son of a wealthy Milanese industrialist who was keen to expand upon his father’s success. Fresh out of engineering school, he bought a small maker of refrigerators and space heaters in Genoa called Isotherm that had come up with a cheaper, simpler way to manufacture the things. He built the company up expanding their market to outside Italy. The success allowed Renzo to indulge his love of motorized speed.

He raced motorcycles, cars, and boats, once winning the famed Pavia-Venezia power boat race. He was also savvy enough to keep his company running throughout the Second World War when Mussolini and then the Nazis sucked dry and destroyed Italy’s industry. In 1942, after his factory was damaged by Allied bombs, he moved the business to an 18th Century family villa in the small town of Bresso to protect it from advancing armies. A year later, with the help of loyal locals, he hid the company’s assets from the retreating Germans who were taking whatever they could from the beleaguered Italians. After the war ended, sales of refrigerators and heaters declined. They were luxuries people just couldn’t afford. Renzo had already been thinking of a way to transition the company to his passion, things with engines, and saw an opportunity in a desperate need for cheap transportation after the war.

While at the Milan Exposition in 1947, he saw a small scooter called the Furetto (Ferret, in English, which is a great name for a scooter) that was being built by the tiny Giesse company. It was basic and pretty stupid looking, and I don’t know what the man who would later give us the Iso Grifo saw in it with its minuscule 2 horsepower 65cc motor. But, somehow, Renzo recognized potential and bought the company, moving its production line to Bresso. Along with the scooter came its designer and engineer, Gianfranco Scarpa. When the Furetto went on sale as an Isothermos in 1948, the underpowered, rickety thing was an utter failure. With the sleek and stylish Vespa coming out at the same time, the ugly Iso didn’t stand a chance. An embarrassed Renzo would demand a bunch of unsold ones be buried and ordered Scarpa to completely revise the thing.

The scooter got a more substantial frame and body, and an all new 125cc split cylinder two-stroke that was built in house and based on an auxiliary motor used to start Fraschini aircraft engines. The double piston made the engine more efficient by making sure that all fuel is burned in the cylinder, as well as producing more torque, especially at low speeds. The new scooter was a big improvement, but its looks were no match for the Vespas and Lambrettas that were suddenly buzzing all over the country. Still, while expensive, they were well built, and sold in enough numbers for Renzo to expand into more models. He dropped the “thermos” part of the name since it was confusing, and began producing small motorcycles called Isomotos; and Isocarros, three-wheeled utility vehicles.

Larger, more powerful versions of the twingle engine were also made. Renzo Rivolta was finally in the motor vehicle business. But, as a new decade began, he knew the future wasn’t in things with two wheels that left the driver out in the open. The war-weary public, however, couldn’t yet afford proper cars. So, Rivolta wondered if it was possible to build something that was halfway between a scooter and a car. Primitive microcars had begun to appear in Germany and France, and Renzo knew that Fiat was in the process of coming up with a replacement for the venerable Topolino. So, when he was approached by an engineer wonderfully named Ermenegildo Preti who had an idea for a completely unconventional vehicle, he jumped at the opportunity. Preti was a prolific builder of glider planes who also understood the need for cheap transportation and wanted to come up with a solution. Italian cities being what they are, he decided to try and design the most compact, and inexpensive, car possible. One of his his first ideas was to do away with two side doors in favor of one front door, which kept the width down to the exact size of two (small) adults and one child sitting shoulder to shoulder to shoulder. So, no, it wasn’t a refrigerator that inspired the Isetta’s door.

Preti had actually used this idea on one of his gliders, the AL 12, which had a nose that was hinged on one side exposing the cockpit. Expanding on this idea, he figured it would be safer if all occupants could exit right onto the sidewalk, so he made his design as short as possible. The production version would be just 7’ 6” long, so the car could be parked nose to the curb. When Ermenegildo showed up at the Iso factory with a scale model of his idea, Rivolta’s secretary cracked up and reported that some nut was there carrying a wooden watermelon. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like any of Preti’s original designs, or wooden watermelons, exist, but I can only imagine it must have seemed like an insane idea. But, so crazy it just might work. To make improvements on Preti’s idea, Rivolta hired a young designer named Pierluigi Raggi, about whom not much seems to be written, unfortunately, although both guys are described as “volcanic.” Apparently Preti would come up with ideas and rough sketches, and it was Raggi who turned them into something workable. Preti was never happy with how Raggi interpreted his ideas, and Raggi thought Preti should have stuck to planes without engines. None of the original drawings, or prototypes seem to exist, so it’s hard to tell how the design evolved. But, one of Rivolta’s demands what that on the inside, the car should be as comfortable, and conventional as possible. As with his later cars, he thought it should be designed from the inside out. Whatever the exact process was, they definitely thought outside the box. They seem to have started with two people sitting on a bench with a door in front of them and then encased them in an egg. No boxes whatsoever.

To keep to Renzo’s demand for operational orthodoxy, it has a regular ol’ steering wheel, and the gear shift layout is a normal H-pattern; both features that weren’t present in a lot of micros like the Messerschmitt. The brakes are hydraulic, and it has 12v electrics. Suspension up front is a fancy Dubonnet type, with leaf spring in the rear.

At the suggestion of Giovanni Michelotti, they also gave it as much window as they could. There’s wraparound plexi in back, and big side windows. All cars would also come with a large, cloth sunroof. All this openness gave you the feeling of being in something bigger than you were. It has a light, but sturdy, tubular triangle frame; and 10” wheels which made it much more stable than cars like the Fuldamobil which used 8 inchers. The engine was a version of the twingle from the Iso 200 motorcycle expanded to 236cc’s and making 9.5 horsepower. The first drivable prototype was completed in 1952 and it was actually a 3-wheeler. Everything worked so well that they shredded the rear tire, so they decided to add a fourth wheel. But, the back wheels were positioned close together to add stability without the need for an expensive, and heavy, differential. One of the car’s cleverest features, thought up by Preti at the last minute, was a universal joint at the bottom of the steering column to allow it to fold way with the door making getting in and out easy. Also, the engine, in a way that could be described as MR, was placed on the right side of the frame in order to counter balance the weight of the driver. It was attached to a 4 speed transmission that drove the rear axle with two chains. The body is shaped steel welded to a tube skeleton. Raggi gave it the accent line down the side to create fenders and alleviate the watermelon effect. One of the coolest features are those shark gill vents on the engine cover.

The Isetta was first presented to the public in the fall of 1953 at the Turin Auto Show and it was a mindfuck as you’d expect. No one had really ever seen anything like it. Messerschmitts had been on the road in Germany for only a few months, and most Italians had never seen one. So something as tiny as an Isetta that actually kept you out of the weather was a revelation. And it had a certain stylish charm that made it like a Vespa of cars. It was priced slightly lower than a Topolino at the equivalent of $650, which was affordable for a lot of people. Renzo expected to build 50 a week and said the price would drop after production ramped up. However, Fiat, which was in the process of developing the 600 at a cost of about $100 more than the Isetta, objected to the Italian government which put pressure on Iso, so the price never changed.

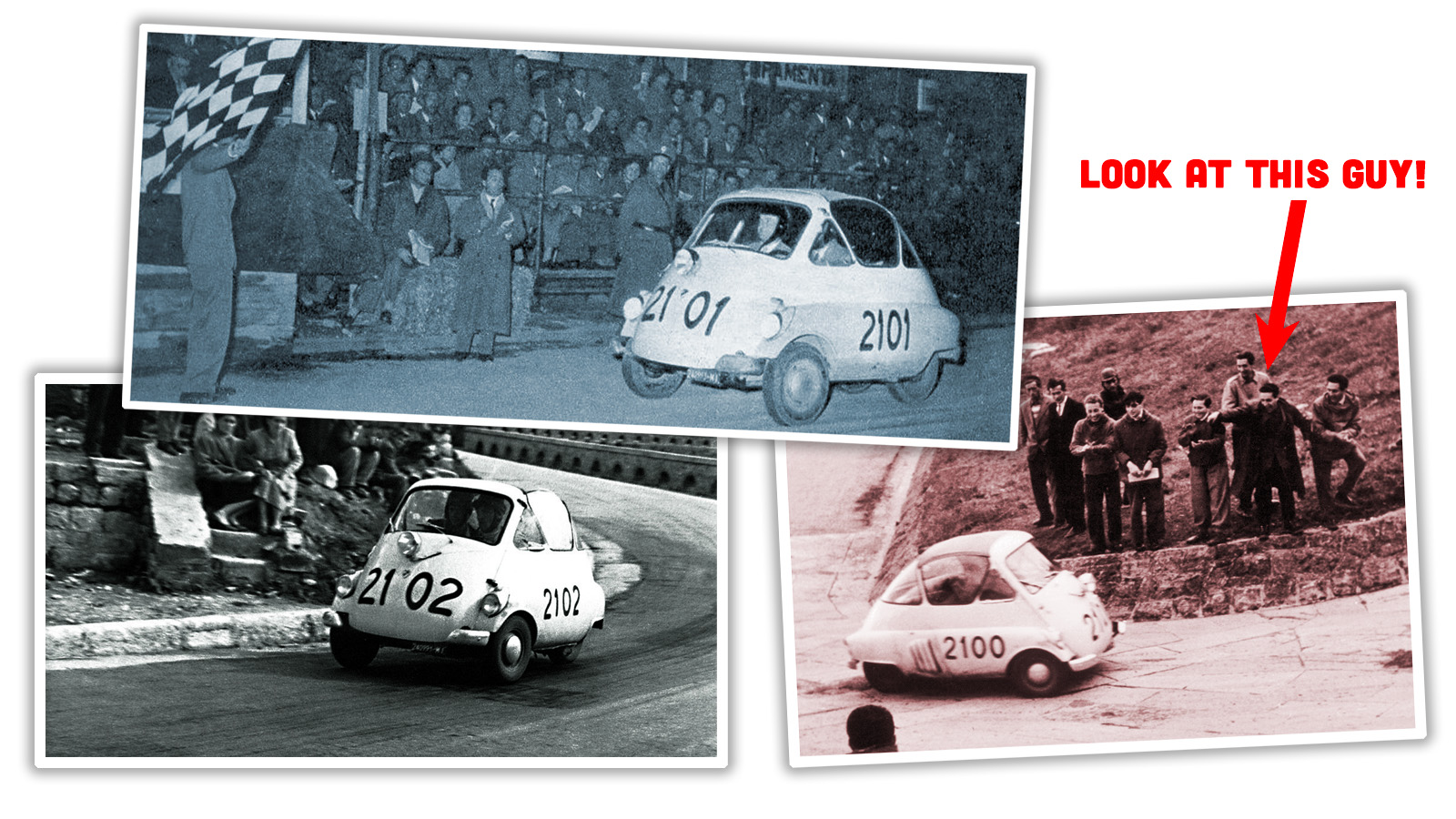

Renzo knew he was on to something, and felt the little car could solve the problems of cities all over the continent. He also knew that the pressure from Fiat meant that the Italian market was going to be limited, and he was right. So, he also showed the Isetta in Paris and Geneva where it was every bit as much a sensation. The international press raved about the car with England’s The Motor saying, “Boldly and cleverly unorthodox, simple but by no means crude, diminutive but quite good looking, the Isetta may well prove to be pioneering a development as important as that of the motor scooter…” They even loved the way it drove saying, “Fast cornering reveals complete stability, with little body roll and quite a definite under-steer characteristic.” Of course when you say, “fast cornering” in regards to an Isetta, the “fast” part is relative. Still, sounds like a hoot and I can attest that it is. Driving an Isetta is as unique an experience as you’d expect. 0-30 (yes, 30) takes about 13 or so seconds, but that doesn’t really matter when you’re in something the size and shape of a giant pumpkin. The steering is really quick and direct, and these Italian cars had a really nice gearbox, believe it or not, with synchros on each gear. Of course, you’re acutely aware of the fact that there is no car in front of you, just your knees, and some thin steel and glass. To the public, the Isetta was something out of science fiction. A cutting edge look at the future, and is like a space pod compared to the ancient Topolino and the other prewar jalopies sputtering around the countryside. Plus, it was light years ahead of other microcars in terms of refinement. But, for whatever reason, initial sales were slow. Outside the box looks good from inside the box, but venturing out there is scary. As ordinary as it may have been to drive, it still looked like an egg. In 1954, to promote the car, Rivolta entered four Isettas in the Mille Miglia endurance race. They started first and finished last, but all four cars did complete the 1,000 mile race, averaging 43 mph, a pretty remarkable achievement. They were awarded special trophies for the being the coolest cars in the race, no joke. The publicity didn’t help. And, when Fiat came out with the 600 and 500 in succession, the Isetta was doomed in Italy. But, Renzo always had his backup plan. At that motor show in Geneva there was another car. The V8 powered BMW 502, another sales flop. Iso sold only around 5,000 Isettas in between 1953 and 1956. But, Iso obviously wasn’t done. And neither was the Isetta.

One of the great things about the postwar microcar boom was that it totally democratized the automobile industry. At least, everywhere except America. Since regular cars were financially out of reach for the masses, and most car factories were demolished anyway, anyone who could fabricate something vaguely car-like could become an automobile manufacturer. The public was hungry for cheap transportation, so all you needed was some wheels and a motorcycle or scooter engine, some DIY engineering skills, and whatever scrap you could cobble together. And, who knows, if you hit on something the public liked, maybe you could eventually compete with the big boys. This then forced those big companies like BMW and Fiat to produce cheap cars, something they hadn’t really ever done before. Or, at least in many decades. It was a rebirth of the auto industry and, like in the early days, everyone was welcome. This gave us cars the likes of which had never been seen before, or since, and led to an explosion of innovation. Similar to today where necessity is giving us incredible advances in technology when it comes to efficiency, manufacturers of the ’50s learned how to make cars whose primary feature was their thriftiness. And, they had to make this transition quickly, all while rebuilding their factories, to prevent them from being left behind. So, that’s how we got a car which was like no other that was something of a collaboration between one of these new, cottage industry carmakers, Iso, who would go on to build cars that rivaled the big marques; and BMW, a relative Goliath who needed to keep up with the Davids in order to survive. At the 1954 Geneva Motor Show that saw the debut outside of Italy of Iso’s Isetta, BMW had on display its new 502, a gorgeous car powered by Europe’s first V8. It was a vehicle almost no one on the continent could afford to buy, not to mention keep running with gasoline still scarce and expensive. After the war, most of BMW’s manufacturing capabilities had been dismantled, all the machinery and tooling handed over to the Allies. Plus, one of their main factories in Eisenach was now situated on the other side of the Iron Curtain. In 1948, they were permitted to resume production of motorcycles, building 250cc powered bikes from parts mostly left over from before the war. People were so desperate for any kind of motorized transportation that they sold everything they could build, so the company stayed on its feet, if only barely. When they finally had the means to build a proper car, they actually did first think to make an economy car. The 531 was basically just a spruced-up, modified prewar Austin. Primitive, but that’s all that people could afford. However, when Hanns Grewenig was put in charge of BMW, he decided he wanted a luxurious car to be a “calling card” for not just the company, but all of Germany. Notably, the opposite of what Volkswagen was doing. So, they produced the 501, an almost completely hand built, exquisite car powered by a 65 horsepower straight six. It cost between 13,000 and 15,000 Marks, over ten grand more than a Beetle. That would be the cheapest car BMW offered. As they put more models into production, the finest ones pushed 40,000 Marks. But, these were barely updated prewar designs and people who paid that kind of money wanted something much more modern than the staid, old fashioned looking cars BMW built. Add to that the fact that by the mid-1950s, demand for motorcycles had tanked as people wanted something with protection from the weather, and BMW was in dire straits. They couldn’t sell enough vehicles to keep the production lines open. They toyed with the idea of producing a Vespa-like scooter. It was called the R10, and they built a few pretty prototypes, but rightly decided that there wouldn’t be enough profit margin, and the scooter craze had pretty much run its course anyway.

Back in Italy, Renzo Rivolta wasn’t selling enough cars himself to build his company into what he envisioned for it and Fiat was too powerful in Italy for Renzo to compete with. So he needed a way to get his Isetta into the rest of Europe. Exporting was too much of a hassle, and he wanted to transition his factory into building full-sized cars. He needed to sell licenses to manufacture the little Isetta. He knew it was a winning, modern design. The cars his company had built were well received. So, he took the Isetta on the road and ended up at that Geneva show. Right alongside the car he was running away from, the Fiat 600. The Isetta definitely caused a stir. Weird, little microcars were just starting to catch on, and the egg shaped Isetta was was one of the weirdest. A single door in front, that bubble like greenhouse. It didn’t look like a car. But, it was comfortable, well made, and incredibly practical, being purpose-built for a poor country in the midst of reconstruction. One of the first people to be taken with it was the Swiss importer of BMWs. He knew the company had finally thrown in the towel on the big old-fashioned cars and was looking at starting the long process of again attempting to design an affordable car. And, here was one ready to go. He immediately called Hanns Grewenig who then sent head of development Eberhard Wolff to Italy. Grewenig wanted to act fast and get the best deal before some other desperate German company beat him to a license. This was a win-win for Renzo Rivolta. Firstly he needed the cash; and second, BMW, despite flagging sales, was a company with a good reputation and distinguished history, and they would lend legitimacy to Iso.

When Wolff reported that the car was actually good, legendary engineer Fritz Fiedler joined him in Iso’s home of Bresso, Italy to hammer out the details. Fiedler decided against licensing the Iso twingle motor. It wasn’t particularly reliable and, at 9.5 hp, he felt it was underpowered go figure. BMW had plenty of experience with small engines, and only licensing the body design would save some money. Grewenig was still skeptical. He knew his designers could come up with something much better than this watermelon shaped contraption. But, it was so cheap to produce, and Rivolta was willing to sell all the tooling, so the initial investment was tiny. Exactly what the cash strapped company needed. At the very least, it would serve as a stopgap until BMW could develop its own small car. So, the deal was signed and one of the finest makers of luxurious motorcars the world has ever known began producing the cheapest, most basic and funny looking car ever.

Fiedler made a few refinements to the original Italian design. He raised the headlights into mounted pods, and smoothed out the cooling fins. He also added a heating system, and changed the suspension from rubber pads to steel helical springs. Most importantly, the car got a robust single cylinder, 250cc motor derived from the R25/3 motorcycle engine. It made 12 horsepower and was a four-stroke unlike the original’s two-stroke Iso unit. 250ccs was also the cutoff for a special reduced tax driver’s license which meant a built-in market. The motor was connected to a 4-speed motorcycle transmission adapted to have a standard H pattern with an added reverse gear. As they converted part of their factory to begin production, word got out that BMW was coming out with Germany’s cheapest automobile. A stunning development in a country starved for cheap autos. Even the Volkswagen was too expensive for the lower class; it was considered a middle-class car. And, other makeshift microcar makers produced cars in such small quantities, they practically didn’t exist. So anticipation was high for the German Isetta when it was released to the public in April of 1955.

The reaction was better than BMW had hoped. Everyone loved it. It was so much more refined than other microcars of the time like the crude Fuldamobil and rickety Kleinschnittger. The Isetta, by comparison, had many creature comforts. Climate control, electric start, a comfortable bench seat and it drove well. The suspension was sophisticated for such a tiny car, and care was taken to keep noise and vibration to a minimum. In their review, Das Auto wrote [translation by Google], The engine, while underpowered, had the torque of a 4-stroke, so was good enough in city traffic. It also got up to 60 MPG. And, because BMW could produce it in larger volumes than the small manufacturers, the price was unbeatable: 2,550 Marks. It was cheaper than some motorcycles and it kept you dry. BMW sold 50,000 in less than a year. The Isetta had arrived just in time to take Germany by storm. Because it cost so little, BMW wasn’t making much profit on each one, but they were pumping them out in numbers that let it pay for itself which meant the factory could stay open, and the company could concentrate on the future.

If it wasn’t for the Isetta, the Neue Classe may never have happened. The German government at the time wanted to consolidate its auto industry and was pushing for companies like BMW and Auto Union among others to merge, which is how we got Audi. But, BMW resisted, knowing it had solid markets at both ends of the spectrum. By selling thousands of Isettas, the pressure was off the luxury cars, which BMW could then refine and improve. And they could also go full speed on a truly modern economy car that would mean an end for things like the Isetta. But, before they could get there, their little egg needed some upgrades. The engine was expanded to 300cc’s for drivers who didn’t have a special license. This gave it a face peeling 13 horsepower which was actually a huge improvement. They also made it a little more livable inside. One drawback of that bubbly greenhouse was that only the small, triangular window opened and it got pretty stuffy in there especially if it was raining and you couldn’t put the sunroof back. In 1956 they gave it sliding windows which were a big help and made it feel more like a real car. The suspension was also improved with longer swingarms, larger springs, and new telescopic shock absorbers. BMW also began exporting Isettas, and even selling their own licenses. Isettas were built in Great Britain in both 3 and 4 wheeled form. These in turn were exported to Canada and Australia. A U.S. version with big headlights came to our shores. Here it was considered a toy. People would have one on their yacht, or use them around the estate. They were even repurposed as golf carts by the Chadwick company. Road & Track found the Isetta surprisingly “rugged” and went on to say “It is well designed, well built, and it does its job efficiently.” Fair enough. BMW would also use it as the basis of a “normal car.” They really needed something above the Isetta’s price point to bring in some money. So, in 1957, they did a quick and dirty design by lengthening the Isetta to include a back seat and a rear door. The 600 used BMW’s legendary 582cc boxer twin, and had rear wheels in a normal track. It had an all-new chassis that would be the last separate chassis on a BMW, and the company’s first semi-trailing arm rear axle. It was really quite a well engineered machine especially since its development time was only a matter of months.

It’s also an amazing use of space. It’s quite teeny, but inside feels as roomy as any other car. I’d actually much rather ride in its back seat than a Beetle’s. The front door is more of a hinderance in the 600 since it can’t be parked nose to the curb like the Isetta. But, it’s a cool quirk, just one that actually doomed the car. As clever as the 600 was, by the time of its release, buyers didn’t want quirky any more. Hans Glas had released the Goggomobil, a microcar that looked like a shrunken normal car, and it was gobbling up Isetta sales. Plus, used Beetles were starting to hit the market in numbers that made them affordable. They tried putting an auto-clutch in the 600 to garner more sales, but it didn’t help and production of the “big” Isetta stopped after just 2 years with only 35,000 sold. It was a flop, and a painful one. The little Isetta, though, would keep on in Germany until 1962 with over 161,000 built. An impressive amount for a tiny little pod. In 1959, BMW would release the 700, a unibody masterpiece designed by Michelotti. Like the 600, it had a rear-mounted boxer engine and much of its technical design was an evolution of the 600. The 700’s success revitalized BMW and secured it as a modern company. It would then lead to the 1500 which was basically the birth of the company we know today. A company that still has in its roots a funny little egg with one door.

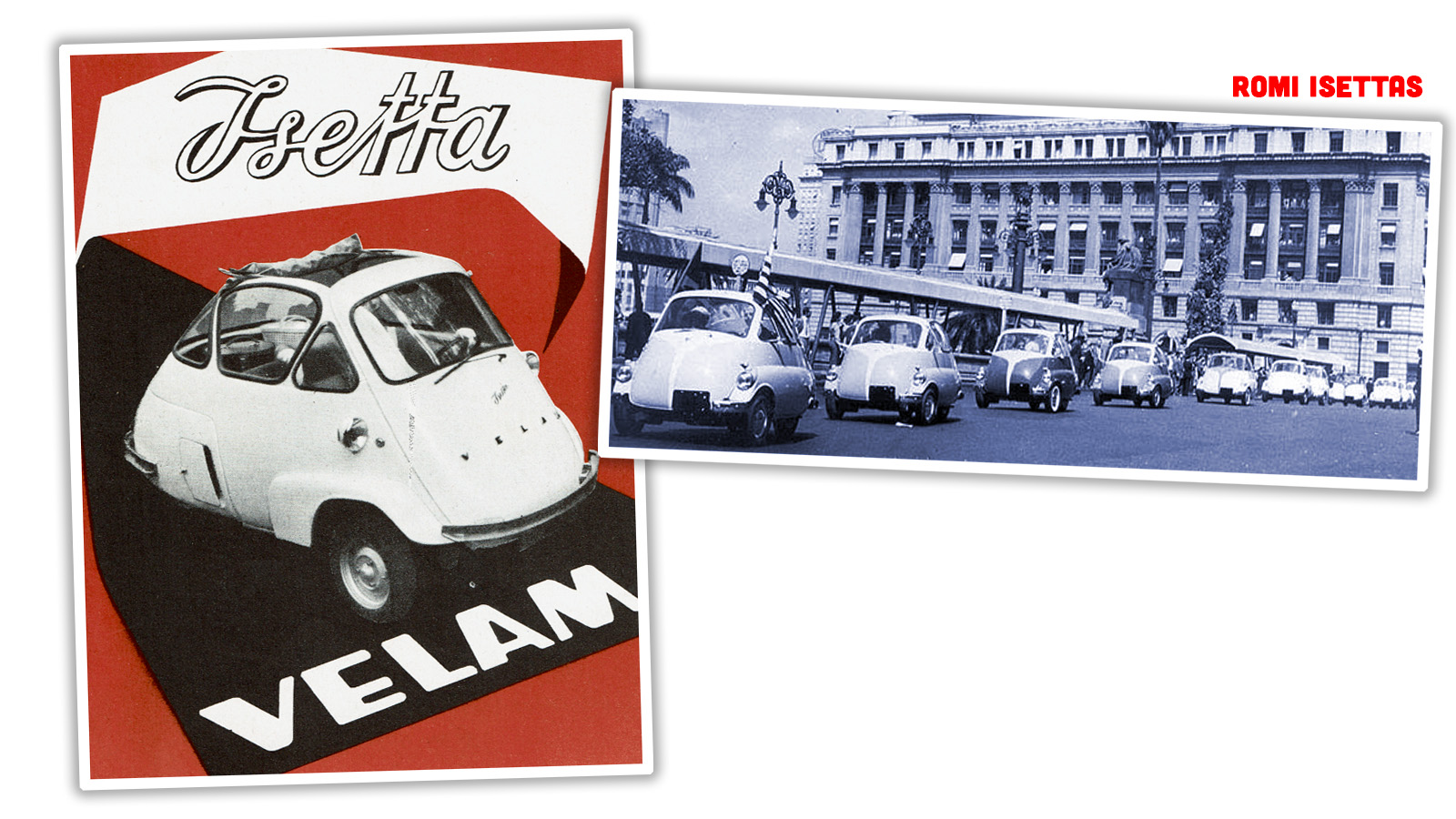

There are many footnotes to the Isetta story. As they were selling the license to BMW, Iso sold the entire assembly line to a company in Brazil. Romi was a machine tool manufacturer and its version of the Iso car was the first automobile manufactured in Brazil. For the first year, they were powered by the original Iso motors, but then they switched to more reliable imported BMW 300 engines. 3,000 Romi Isettas were built between 1956 and ’61.

Since all the machinery was now in South America, when the French company Velam bought the rights to the Isetta from Iso, they had to completely redesign the car. Because they were French, their version had its own set of quirks. Its shape is much cleaner than the Italian and German versions being almost symmetrical front to back. It was also monocoque with a subframe to house the motor. Also, as far as I know, it is the only car in the history of the world to have 11” wheels. So, it’s absolutely impossible to find tires. The speedo is also mounted in the center of the steering wheel which makes it hilariously impossible to read most of the time. Belgium has the honor of having built three different versions of the Isetta. First was original Iso Isettas meant for the Dutch market. Then, Velam built some of their cars there. And, finally, towards the end of the run, German market Isettas were constructed in Belgium since the ones built in Germany were meant for export. So, the Isetta truly became a global car, even before the Beetle had. Today, they’re one of the most instantly recognizable, and collectible, cars in the world. It helped establish two renowned car companies. And, it put people on a war torn continent to work, and back on wheels. What happened to Renzo Rivolta and his company after he licensed the body design to BMW? That was probably mine! My father bought one in 1983 and right now I would like to sell it (in Germany). We had lots of fun with it but I really don’t enjoy it enough to keep it The World needs new light car rules, there has to be something done to fit vehicles in between motorcycles, scooters, golf carts/neighborhood cars and the energy guzzling 5000 lb plus “safety” tanks out there. I’d risk it if it was legal. My plans for the future are an upgrade to 13 peak horsepower, 100+ mph top speed, 0-60 mph acceleration comparable to a modern 4-cylinder car, integrated roll cage, and other changes that will make this a much more practical vehicle. The finished vehicle will remain pedalable, by being kept under 100 lbs. Should this prove to be practical for daily use, I’d love to make a car version with no pedal drivetrain, that has a hub motor in each wheel for all wheel drive, and which makes more than 1 horsepower per pound of vehicle. Math suggests it is theoretically possible to make such a vehicle accelerate from 0-120 mph in under 5 seconds, and if it could be mass produced, it would cost somewhere between a moped and a cheap motorcycle. And you’d be able to do hundreds of miles of travel for literal pennies. Of course, legal/bureaucratic nonsense is in the way of such a thing becoming a mass market reality. I get away with mine because I took advantage of the way vehicles are defined in the legal code, and have my vehicle perfectly functional as a “bicycle” with the motor disabled. I look at the vehicles built for the Shell Eco Marathon and the Electrathon races as a guide to what sort of efficiency and compact designs are possible in a motorized vehicle, and I look to velomobiles as a guide to what sort of ultimate aerodynamic streamlining and weight reduction can be achieved in the real world. Single-seater vehicles that get thousands of miles per gallon are possible with modern knowledge of aerodynamics and composite materials. Such vehicles are not a good fit for today’s environment of wasteful, overweight road hippos, and corporate/government bureaucracy run amok that conspire to keep such things off the roads, but the resources to support the current reigning paradigm probably won’t exist in perpetuity. Given recent geopolitical trends, it’s quite possible we could collectively find ourselves in a situation similar to the post WWII era in the coming decades. Should that come to pass, we’d have to start over with regard to automobile manufacturing and our perception of what a car is. The good news is that should this come to pass, energy scarcity really shouldn’t be an issue for fueling transportation no matter how scarce energy becomes. Individual rapid transport that gets literally thousands of miles per gallon at interstate-appropriate speeds is perfectly possible, with yesterday’s technology. I own both a British built Isetta and a BMW 700. The Isetta restoration is done and the 700 is under the knife. Amazing cars and wonderful history! To say that I’m thrilled to have them in my collection and be able to restore them is a huge understatement! It’s very special to be able to have both these rare and historical rides, not to mention the family history they represent. Nevertheless, Isettas don’t drive well. We owned two, I never enjoyed it. Of course our 3 wheel isetta is even more special. I drove it like two times, totally hated it. On the other hand I used to enjoy sitting next to my dad driving it. He really knew how to deal wit that little thing and drove it very fast. We had some really funny situations, like when the brakes broke while driving and we had to brake by driving off the road into a small hill next to it and nearly rolled the Isetta. Lots of memories, but since my dad passed away, my motivation to care for this car has gone, too. Unfortunately due to the three wheels it seems nearly impossible to sell it, unless I sell it for a rather low price…